As you know there are plenty of scales throughout the world, and I want to highlight a few here. Whether as a classical style composer or someone just interested in creating music, being exposed to more types of scales will broaden the music you create. In order to get the most out of this article, you will need to understand intervals.

The seven scales you should know are:

- Whole-tone scale

- Chromatic scale

- Hemitonic – pentatonic scale

- Anhemitonic – pentatonic scale

- Hexatonic scales

- Tetratonic scale

- Octatonic scale

Of course, there are many more scales to explore – from microtone scales to the scales found in nature! But hopefully, this will be a nice look at scales you don’t typically encounter.

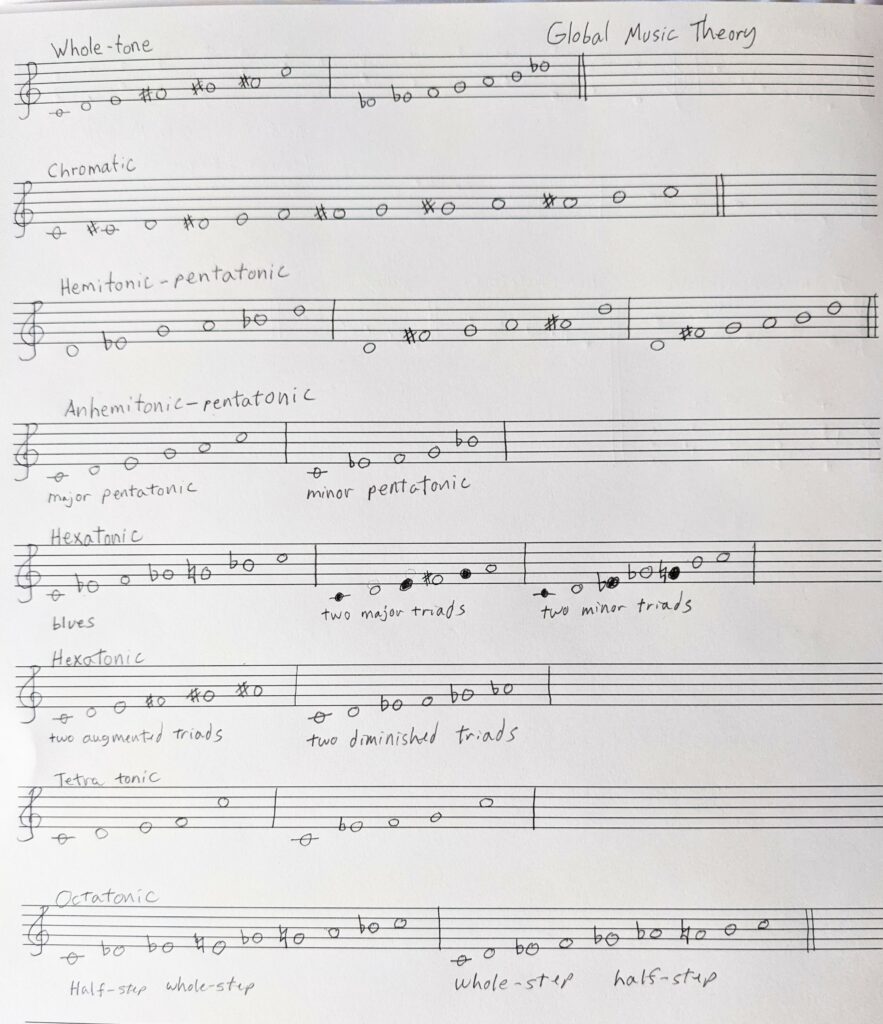

Here is an image of all the scales I talk about in this article:

I find improvising with these scales helps to unlock new ideas and sounds.

What is the whole-tone scale?

This is a simple scale to understand. It consists purely of whole tones, no half-steps. You can find many examples of composers using this scale. Since this scale consists of 6 notes, it’s actually under the Hexatonic scale category but I thought it could use its own example because it has been used in many pieces of Western classical music such as Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune.

The whole-tone scale is commonly used to create a “dreamy” sound.

There are only two versions of this scale, one starting on C and the other starting on D♭.

c – d – e – f# – g# – a# – c

d♭ – e♭ – f – g – a – b – d♭

Whole-tone scales sound less driven toward a goal because they lack a leading tone. Every interval is equal so composers either playing with the fact that the music does not demand to go anywhere, or they find other ways to create a “tonic” note.

A whole-tone scale can temper expectations and just let the music breath in a different way than a typical major or minor scale can.

I’m sure music from other musical traditions have used the whole-tone scale, but I’m ignorant to those that do. I’ll keep my ears out for some examples to place here.

Chromatic Scale

In the equal temperament tuning system, the chromatic scale consists of 12 pitches equally spaced by half-steps (semitones). Of course, not all tuning systems are tuned to be a series of 12 equal half-steps. Some traditions, such as Indian music, tune using just intonation (just intonation is a tuning system that uses simple ratios rather than the complex ratios required to cut an octave into 12 equal pieces). A chromatic scale in just intonation will not have equal half-steps but it will still contain 12 pitches.

Like a whole-tone scale, the chromatic scale has a difficult time establishing a “tonic” pitch because all intervals are the same (no leading tone). The chromatic scale in its entirety is rarely used, except in 12-tone music where it is exploited to the fullest degree. This is not to be confused with chromaticism which has been a feature of music since the beginning, it just may not have been called that. Chromaticism is when a composer introduces pitches that are outside the key. Since the voice can easily slip around pitches, human surely sang with “chromatic” inflections whether intentionally or not. To me, the difference between using the chromatic scale and chromaticism is that if a piece uses the chromatic scale, it actively uses all 12 pitches with no key center. Whereas chromaticism has a key center and notes are going in and out of the key. Highly chromatic music might use all twelve tones, but if it is still using the language of a key, then it is chromaticism not using the 12-tone scale.

For a fantastic example of early chromaticism, here is Carlo Gesualdo’s Sesto libro di madrigali. Just look at all the accidentals and lines moving by half-step. This is a great example of a composer not using triadic harmony but using counterpoint voice leading and their ear.

Hemitonic – pentatonic scale

Pentatonic scales are awesome! They seem to be an almost universal of human musical expression – they are found everywhere and at all times. According to Michael Spitzer (his book The Musical Human is very interesting) a bone flute dated around 40,000 BC was found and it has five finger holes to play a pentatonic scale! Here is Wulf Hein playing a reconstructed bone flute.

Pentatonic means there are five pitches that make up the scale within an octave. Pentatonic scales come in a variety of flavors so here is but one large group – hemitonic scales contain one or more half-step (semitone).

d – e♭ – g – a – b♭

Of course, you can place the half step(s) anywhere you like.

d – f# – g – a – b♭

d – f# – g – a – b

Anhemitonic – pentatonic scale

Another flavor of pentatonic scales are those with no half-steps – anhemitonic. Here are a couple of examples:

c – d – e – g – a = major pentatonic

c – e♭ – f – g – b♭ = minor pentatonic

These can be grouped into major and minor. These scales are commonly used in rock and blues music. A blues scale just needs the “blue” note – the g♭ in the example below.

c – e♭ – f – g♭ – g – b♭

As long as you know the intervals used in the scale, you can transpose these to any starting pitch.

Intervals of a minor blues scale: m3 – M2 – m2 – m2 – m3

Hexatonic Scales

These are six note scales. As with any scale it just means a collection of pitches with certain interval relationships. So, any six notes within an octave can be a hexatonic scale. With that said, it should be clear there are many hexatonic scales (including the whole-tone scale mentioned above). Below are just a few of the more common ones.

Blues scales

Blues scales can be viewed as a pentatonic scale with an added “blue” note. If you are a guitar player, check out this fantastic article with tons of examples https://www.jazzguitar.be/blog/blues-scales/

Here are the minor and major blues scales.

Many of the hexatonic scales can be made by placing mutually exclusive triads (triads that don’t share pitches in common) on top of each other. For example, two major triads would be:

c – e – g + d – f# – a = c – d – e – f# – g – a

You can do the same with minor triads:

c – e♭ – g + b – d – g♭ = c – d – e♭ – g♭ – g – b

Or augmented triads:

c – e – g# + d – f# – a# = c – d – e – f# – g# – a#

Or diminished triads:

c – e♭ – g♭ + d – f – a♭ = c – d – e♭ – f – g♭ – a♭

Tetratonic Scales

These scales only have four notes to the octave. As with the other scales there are many possible scales that can be built on just four notes. These scales are not as common in modern day music. Four-note scales were more commonly found in ancient humans, though not as widely spread as pentatonic scales. Michael Spitzer writes about the importance of tetrachords in how early musicians organized and built the seven note scales that came to dominate Western music. The ancient Greeks used the interval of the perfect fourth as a building block for their music. A tetrachord is filling in the gaps of a fourth. For example, the following tetrachord spans the interval of a perfect 4th (c to f):

c – d – e – f

The Greeks would then layer on the next tetrachord:

g – a – b – c

And that gives us the C major scale.

Spitzer goes on to express the importance of the interval of the 4th up until changing tastes preferred thirds.

Here is an example of a tetratonic scale:

c – e♭ – f – g – c

When playing around with these intervals, I inevitably end up with an “old” sound.

Octatonic scale: Alternating half-steps and whole-steps

This one is pretty self-explanatory, just pick a pitch and decide to begin with a half-step (semitone) or a whole-step (whole-tone) and keep alternating until you reach an octave. For example:

c – d♭ – e♭ – e – g♭ – g – a – b♭ – c

c – d – e♭ – f – g♭ – a♭ – a – b – c

These are members of the octatonic scale family because they have eight notes.

There are many more scales to explore and when you add in the variable of different tuning systems and microtones the number of possibilities explodes!

Leave a Reply