In this article you will learn how to write a 1st species counterpoint in 6 steps. I also strive to bring a deeper understanding around some of the “whys” of this practice.

Why you should learn 1st species counterpoint

Counterpoint is the foundation of Western music polyphony (multiple melodic lines of music). 1st species counterpoint is a great way to begin to understand and manage two voices. It is a methodical way to build a second part from a melody. Learning counterpoint is a fantastic way to hear how intervals interact vertically and how to handle melodic lines horizontally.

Whether you are composing in a classical style or writing pop songs, counterpoint can be an incredible tool to have ready to use. Counterpoint can be used as a way to generate ideas, or work to develop a piece. I believe it offers a method to explore music creation in a way improvisation and other compositional methods may not excel at.

Be sure to download this free counterpoint workbook!

Related articles

Prerequisites before writing:

What are perfect and imperfect intervals in counterpoint

Consonance refers to the intervals between two notes that are deemed “pleasant” or consonant. Imperfect intervals are more dissonant than the perfect intervals. Dissonance typically sounds harsh where as consonance sounds smooth. This has to do with how the sound waves from each pitch are interacting with each other.

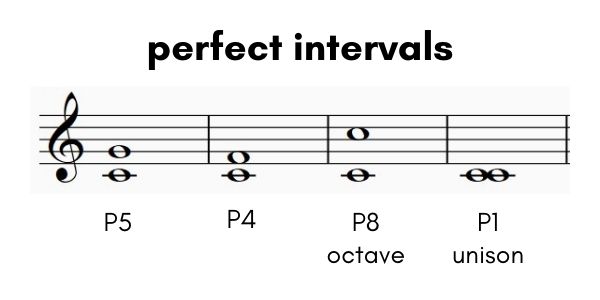

What are perfect intervals?

In 1st species counterpoint the perfect intervals are:

- Perfect 5th

- Perfect 4th

- Octave

- Unison

Why are these considered perfect? It has to do with the complexity of wave patterns when these intervals are sounded. For example, when a C and a G are sounded together, we get a perfect 5th – a consonance. The wave patterns of these two pitches fit into each other rather nicely – meaning their peaks and troughs match often and consistently.

Quick acoustical physics refresher: 1 hertz = 1 vibration per second. Middle C is 261.63 hertz and the next G above middle C is 392 which lets us visualize their wave patterns interacting. In the time it takes C to complete 2 periods G has completed 3 periods and the waves line up again. This gives us a nice ratio of 2 to 3.

What are imperfect intervals?

Imperfect intervals create wave patterns that are more complex than the perfect intervals but not as complex as the dissonant ones. Let’s look at C and E (a major 3rd). In the time it takes C to complete 4 vibrations or periods, the E has completed 5. This makes sense because the E is higher in pitch and has a higher frequency which means it moves faster than the C.

In 1st species counterpoint the imperfect intervals are:

- minor 3rd

- major 3rd

- minor 6th

- major 6th

What are dissonant intervals?

Dissonant wave patterns do not fit so nicely. When C and F# are sounded together we get a tritone (augmented 4th) and it sounds rather harsh. This time the C must complete 12 periods and the F# will complete 17 in the same amount of time and then they line up again. This generates a lot more clashing and takes longer for the pitches to sync up than it does for the C and G combination. In this case we get the ratio of 12 to 17 – a much more complex number than 2/3.

Hopefully, that short break down helps you imagine why we perceive certain intervals as consonant and dissonant. In classical counterpoint, you should employ more imperfect consonances than perfect. Dissonant intervals are forbidden. If you write too many perfect consonances in a row the music will sound empty, and you will most likely be breaking some rule of counterpoint.

In 1st species counterpoint the dissonant intervals are:

- minor 2nd

- major 2nd

- tritone (augmented 4th/diminished 5th)

- minor 7th

- major 7th

The three motions of counterpoint – oblique, contrary, and direct.

There are three types of motion you must understand: direct, contrary, oblique. Each motion has it’s own set of rules. When I talk about motion in 1st species counterpoint, it’s referring to moving from one interval to the next interval.

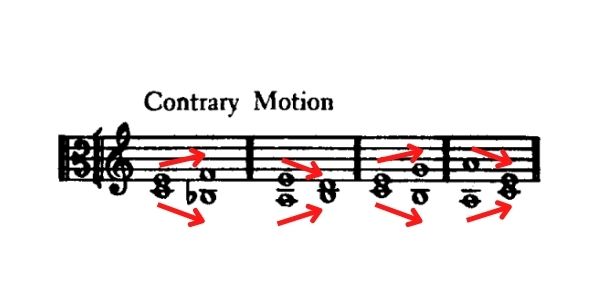

Contrary motion in 1st species counterpoint

Contrary motion is the type of movement you should strive to use the most. With contrary motion you can move from the following types of intervals:

- perfect consonance to a perfect consonance

- perfect consonance to an imperfect consonance

- imperfect consonance to a perfect consonance

- imperfect consonance to an imperfect consonance

As you can see from the example, contrary motion is where the two notes move in opposite directions.

Direct motion in 1st species counterpoint

When using direct motion, you will have to use care not to move too many times in one direction. Here are the allowed and prohibited movements you can make in direct motion.

Allowed

- perfect consonance to an imperfect consonance

- imperfect consonance to imperfect consonance

Prohibited

- perfect consonance to perfect consonance

- imperfect consonance to perfect consonance

In the example the notes are both moving in the same direction, either up or down. Direct motion does not specify that the notes must move by the same interval (that’s called parallel motion). As long as the notes are moving in the same direction it is considered direct motion.

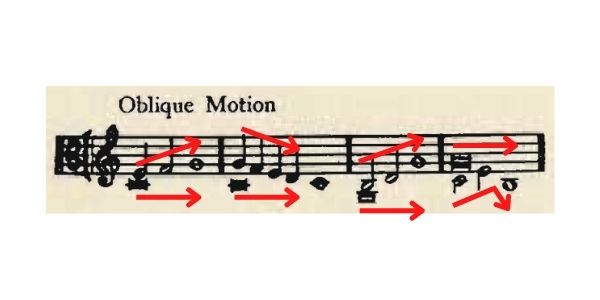

Oblique motion in 1st species counterpoint

Like contrary motion, oblique motion can move to and from any intervals. Unlike contrary motions, oblique is the type of movement you should use sparingly. The allowed motions are:

- perfect consonance to a perfect consonance

- perfect consonance to an imperfect consonance

- imperfect consonance to a perfect consonance

- imperfect consonance to an imperfect consonance

In oblique motion, one note stays the same while the other note moves. Even though one note is remaining on the same pitch you have to watch out for dissonant intervals between the two lines.

The four fundamental rules of counterpoint

These rules are laid out in Joseph Fux’s book Gradus ad Parnassum:

- First rule: From one perfect consonance to another perfect consonance, one must proceed in contrary or oblique motion.

- Second rule: From a perfect consonance to an imperfect consonance, one may proceed in any of the three motions.

- Third rule: From an imperfect consonance to a perfect consonance, one must proceed in contrary or oblique motion.

- Fourth rule: From one imperfect consonance to another imperfect consonance, one may proceed in any of the three motions.

| Perfect | Imperfect | |

| Perfect | Contrary/Oblique | Contrary/Oblique/Direct |

| Imperfect | Contrary/Oblique | Contrary/Oblique/Direct |

5 Steps to compose a 1st species counterpoint

Even though we can lay out how to write this kind of counterpoint in just a few steps, I’d like to impress upon you that this is music not simply robotic-rote learning. You should play back what you write so you can make adjustments to give it some artistry.

Step one – choose a cantus firmus

Select the cantus firmus you will use for the exercise. The cantus firmus I selected is from Fux’s book. The cantus firmus is in the Phrygian mode. (You can also write your own cantus firmus. I go over how to do that here: How to write a cantus firmus.)

I highly recommend singing (or playing) the cantus firmus to get a feel for the shape of the melody before writing the counterpoint.

Step two – write the beginning and end

The beginning and the end must both be perfect consonances. I love the way Alfred Mann translates Fux regarding this:

The beginning should express perfection and the end relaxation. Since imperfect consonances specifically lack perfection, and cannot express relaxation, the beginning and end must be made up of perfect consonances.

-Page 28 from The Study of Counterpoint from Johann Joseph Fux’s Gradus ad Parnassum, translated by Alfred Mann

In general, it is easiest to begin and end with an octave or unison (though a perfect 5th can be used in the first measure).

I highly recommend writing the intervals between the staves. This will help you identify errors.

Step three – write the 2nd to last measure

The next to last bar must be a major sixth if the cantus firmus is in the lower part. If the cantus firmus is in the upper part, then the next to last bar must have a minor third.

In my examples above you can see that I crossed voices (this means the counterpoint went below the cantus firmus) which is fine. You calculate the interval from the lowest pitch up – d to f.

Step four – plan your climax

When the counterpoint is in the upper voice, your climax should be the highest note. When the counterpoint is in the lower voice, your climax should be the lowest note.

Step five – fill in the rest

Fill in the remaining measures but following the Four Rules of Counterpoint.

It’s a good idea to label your motion and intervals when you are just beginning so you can more easily see what is going on in the music.

I have filled in the rest of the measures and analyzed the intervals and the type of motion I used. Instead of presenting a “perfect” counterpoint, I wanted to show how you can improve the counterpoint. There are three things I’d like to point out at this stage:

- Motions: not enough contrary motion (C = contrary, D = direct, O = oblique)

- 3 contrary

- 4 direct

- 2 oblique

- both voices leaping in the same direction at the same time

- a tritone leap from f to b in the 2nd and 3rd measure

I’d start to fix these issues by changing the counterpoint in measures 2 and 3. But like a chain reaction, most of the time when you fix one issue another pops up, so you end up doing a rewrite – like I did below.

I’ll take the same inventory of intervals and motions and see how it comes out.

- Motions: I have plenty of contrary motion

- 5 contrary

- 2 direct

- 2 oblique

- I still have the voices leaping at the same time in measures 3 to 4 but it is in contrary motion which is more tolerable.

I think I’m ready to move on with this version and look for more errors.

Step six – watch out for these rules

The hidden perfect fifths or octaves.

This occurs when you have a perfect interval that is then followed by an imperfect and another perfect. For example:

The above is very poor writing because of the repetitive nature, the consistent motion (direct), and the repeated 5th.

Outlined tritones or leaps by a tritone.

In the 1st red box there is a leap from F to B which is a tritone. Don’t do that. In the 2nd box from the bottom F to the top B the tritone is “outlined”. The A in the middle does not break up the tritone.

Voice crossing is acceptable

You are allowed to have the counterpoint drop below or above the cantus firmus, just make sure it is not for too many notes.

No skips of a major sixth

Pretty self-explanatory…don’t do this.

Unisons can only be used in the beginning and end

You have to be more careful with this when the voices are crossing. Octaves are okay.

Watch out for leaping into an octave or unison even in contrary motion.

If you have to add an accidental to achieve a major 6th or minor 3rd at the penultimate measure, then if that note is used prior it might be good to give it an accidental as well.

In measures 11 and 13 Fux adds raises the F to F sharp. The advice is to not only raise the F in measure 13 but in measure 11 as well.

Continue on to 2nd Species Counterpoint!

Leave a Reply